Last April, Rhonda Jackson, a senior perfumer at Procter & Gamble Company in Cincinnati, started to create a perfume. Jackson had received from the brand’s creative executives her “brief,” the conceptual blueprint that guides the perfumer to create initial “sketches” — olfactory ideas for the creatives to choose from.

There was, however, one thing different about this perfume. Jackson is a perfumer at P.&G. Home Care, and the perfume she was creating was a scent for Febreze, designed to enhance not a human body but an interior space. While Procter & Gamble creates scents for many of the top luxury perfumes, including Dolce & Gabbana and Gucci, the brief for a functional scent, like Oil of Olay or Old Spice deodorant, is driven more by consumer research. To write it, Febreze’s consumer trends specialist, Alyce Nicholson Sheehan, started with the brand’s “key equity measures.” The scent would have to convey “fresh and clean,” and deliver on Febreze’s “proof of claims”: elimination of bad smells. And consumers had to want to use it in their homes.

To come up with what it would smell like, the P.&G. team looked at the point where scent and lifestyle trends intersect, and it struck Sheehan that it was “a fantastic time for lavender.” People are going back to nature, she says, they’re into health and wellness, they’re interested in herbs and simplicity, all of which is associated with lavender. “There’s also a perception that it helps you relax,” adds Mike Kinsey, the fragrance evaluation manager for P.&G. Home Care.

They also looked at the competition and evaluated what Sheehan calls the “plethora of lavenders out there.” Bath & Body Works has a lavender body butter, Walmart sells lavender aerosols, and Airwick does the Relaxation Lavender & Chamomile plug-in. Yet, despite many iterations of lavender, even among P.&G.’s own brands (e.g., Pampers lavender wipes), it was still felt, says Sheehan, that there was room to do a lavender in a way nobody else did. The research told them that consumers wanted pure lavender, that they wanted something “alive,” that dried lavender was a turnoff. So, Jackson’s brief — for a fresh, live, realistic lavender — enabled her to construct around 70 different prototypes, built not for performance on skin but as design elements.

Now, politicial pundits know there is a serious gap between what Americans tell pollsters they believe and how they vote. The same phenomenon occurs in the perfume industry; consumers consistently say they like “innovative scents,” and most leave them on the shelf.

Which is exactly what Sheehan began to find when she queried consumers. Her subject would say she loves lavender and yet, when presented with the scent of a freshly picked plant, would make a face, “Oh, that’s nasty!” “So I try a dry natural one,” Sheehan says. “She hates that too. I do this with around 20 people, and every time, with the lavender you’d smell alive in a field, I get a negative.” The problem is that natural lavender has the strong , rather medicinal scent of camphor. “Consumers only loved the idea of natural lavender,” she notes. “They didn’t like the reality.” Jackson went back to the drawing board, making the creamy lavenders creamier and dialing back the natural lavenders. They spent June testing and questioning. “We started seeing that less lavender was better,” Sheehan says. “And what was strange was the less it smelled like lavender, the more people perceived it as smelling like lavender.”

In August, as they were doing a third iteration, Sheehan remembered that in Jackson’s original 70 she had included some vanillic lavenders that hadn’t been tested because consumers were so focused on purity. So they zeroed in on these, and by the fourth iteration, in September, Jackson had narrowed her sketches to A, B and C.

Into A she put essential oils from the lavandin plant — a close relative to lavender — and a eucalpytus-like synthetic to help the freshness, but essentially left it “live.” For B, she took A and added some floral notes: the synthetics Lyral and Lilial (they smell like lily of the valley); a natural essence of ylang-ylang; some methyl benzoate, for freshness; and eugenol (a molecule found in geranium), for spice and floral complexity. C was about warmth: Jackson inflected A with sweet notes like ethyl vanillin, ethyl maltol (the molecule you smell in cotton candy), fruity nonolactones, a synthetic called Cedrene AC (a cedar scent) and natural patchouli.

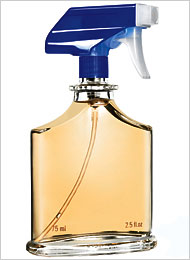

For the final focus groups, Sheehan had A, B and C made into aerosols and had them tested among three groups of 60 consumers in Kentucky, Indiana and Ohio. C was the favorite, bar none. In July you’ll be able to smell a new Febreze. It’s called Lavender, Vanilla and Comfort.