One of China’s hottest sellers is a nonessential Western luxury product that the Chinese have historically never bought and that has virtually no Chinese cultural roots: perfume.

Multimedia

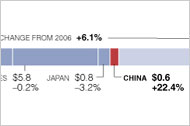

With perfume sales in much of the rest of the world slowing or declining, the industry, primarily based in Paris and New York, hopes for significant growth in China. The market there remains small, though sales are rising exponentially. Nobody knows the exact growth rate, but Patrick de Lambilly, the vice president for Asia for Coty, says, “You can see 20, 30, and 40 percent a year.”

Alexandre de Chaudenay, Asia-Pacific managing director of the perfume licensee Beauté Prestige International, said, “I’d say 20 to 40 percent seems correct, but the figures are extremely difficult, and people tell you anything.”

Still, even if the Chinese market is potentially hugely lucrative, doing business there is far from easy. The regulatory system is uncertain. The complexity of its bureaucracy is daunting. The department stores are of varying quality, and because Chinese tastes are changing rapidly, a store that attracts crowds one day can be deserted the next.

To add to the uncertainty, many in the business say the concept of perfume is so new that a lot of Chinese consumers are, in fact, not buying a perfume but rather the brand to which a bottle of perfume happens to be attached. “China is about brand, brand, brand,” Mr. de Chaudenay said.

And the importance of brand raises the question of the market’s future stability. Although many in the industry talk about the strength of the luxury brands in China, “Are those brands’ perfumes selling well?” Mr. de Chaudenay asked. “I think so. Are the consumers coming back? We don’t know.”

For that reason, Mr. de Lambilly says his perfume company and others are tempering their enthusiasm for the Chinese market with realism. “We’re learning as we go,” he said. “Particularly in fragrances. All of us here are doing the same thing: getting data from the marketing sources, comparing it to other sources, trying to figure it out.”

Hans Wohmann, head of Procter & Gamble’s Asian operations for scent, said sales in China of what are known as “prestige fragrances” — perfumes made by designers and luxury houses like Chanel, Estée Lauder and Dior — were around $120 million versus the $9 billion European market or the $4 billion American market. Even the Japanese market, the largest in Asia, was $500 million in 2006.

As Mr. Wohmann put it, “So 20 percent of the world’s population has only 1 percent of the global fine fragrance market.”

Perfume is a relatively recent phenomenon in China. Mr. de Lambilly said the Chinese started using scented shower products only in the early 20th century. But they were light and simple, he said. “They were for freshening the body and also to avoid mosquitoes.”

Western-type perfumes have been produced in China only since the mid-1980s, said Bill Jin, manager at the PearlChem Corporation in Parsippany, N.J., an importer and distributor of perfume raw materials.

Ralf Ritter, a consultant to the scent maker Takasago, said he would be “surprised if even 50 percent of the perfume bought in China was actually used.” And that, he said, is largely because in China fragrances serve multiple purposes. “They’re fragrances, but they also repel mosquitoes, they have moisturizing properties, and they are used in the summer to freshen up,” he said. “Chinese consumers care that the product does more than just fragrance the body.”

Mr. Jin says there are a just a few local perfume brands. Pearlscent, the sister company of Mr. Jin’s company, based in Guangzhou, is one. “The fragrance concentrates are mainly created by our customers in the U.S. or France and imported from the U.S.A. or Europe.” They are then mixed with alcohol, bottled and sold in China.

Mr. Jin adds that there is virtually universal agreement that Chinese brands will not pose serious competition to Western brands until well in the future. “High-end brands like Dior and Chanel will be for the prestige consumer, which is completely different from the local brand market,” he said. “One bottle of Chanel perfume will cost almost a half month pay for a fresh-out-of-college student.”

Coty entered China, via its Chinese distributor, ADE China, in 2000, immediately establishing Davidoff and its flagship scent, Cool Water, which, Mr. de Lambilly said, is a strong seller. Coty introduced Calvin Klein perfumes in 2006, and that brand is now Coty’s leader. “CKOne is obviously very strong,” he said, “and N2U did very well because it fits very well with the young high-tech mentality of the Chinese.”

Jennifer Lopez, which Coty introduced in 2002, is doing well, and the company has introduced Sarah Jessica Parker’s perfume brand, though Mr. de Lambilly said, “Celebrity brands are not doing that well in Asia.”

Kenzo has been in China for more than a decade and, having developed a stable department store business in the main cities, is now moving into secondary cities. B.P.I. introduced its Issey Miyake and Jean-Paul Gaultier brands in China two years ago.

“We began in Beijing and Shanghai with limited distribution,” Mr. de Chaudenay said, “building up our counters and our visibility with a flagship strategy: we invest more in the point of sale than in media.” In the next three years, B.P.I. plans to start selling its brands in 160 department stores in China’s 20 biggest cities.

Inefficiencies, bureaucratic complexities and the major capital investments needed for setting up a subsidiary have made partnerships with Chinese distributors the norm.

“For regulation concerns, China is still one of the most difficult countries to register your product,” says Sung Kim, regional director for the Asia Pacific Region for Kenzo Parfums. “You need to register for both sales and hygiene. It takes about two months per product, and there is no guarantee that approval will be granted by the authorities.”

Luciano Bertinelli, managing director of Salvatore Ferragamo Perfums, said his company also relied on its Chinese partner to distribute its products. He added, “It is today almost impossible to negotiate China by yourself.” Like Coty, Ferragamo also chose ADE, a 10-year-old company owned and led by May Zhang that works principally on perfume.

The question of which perfumes to offer the Chinese consumer is perhaps the trickiest one. Kenzo, with two huge successes in the Chinese market — FlowerbyKenzo and KenzoAmour — plans to develop perfumes specifically for Chinese tastes. “The Chinese cannot accept strong fragrances,” Mr. Kim of Kenzo said. “They prefer the scent to be more floral for women and more fresh for men.” He said the Chinese also preferred the less concentrated eaux de toilette.

When Prada introduced its original Prada perfume — a powerful, rich patchouli amber — to the Japanese, South Korean and Hong Kong markets, those consumers found it too strong, the company said. So in China, Prada chose instead to introduce Prada Tendre, a much lighter, cleaner version, in March 2007. Prada said the scent was doing well.

Because the brand’s new clean citrus-tinted Infusion d’Iris perfume is proving to be even bigger in Asian markets outside of China than Tendre, the company is hoping for a big hit on the mainland, where Infusion will be introduced this summer.

Mr. de Chaudenay says that companies are not only investing huge sums in getting into the Chinese market, they have accepted huge losses for a long time.

“Your store is good, and the next day a new store opens next door and you lose all your traffic,” Mr. de Chaudenay said. “You’ve invested in your counter, and now your counter is dead. You have to be aware where the market is moving, and it’s moving fast. Very few brands are making money in China, and I mean in all categories.”

But, he added: “We are buying market share. We will get the profits tomorrow.”

Some major Western brands are treading cautiously. Parfums Givenchy, a major perfume brand of the European luxury giant LVMH, is not yet a presence in China. “The Chinese perfume market is tiny,” said Alain Lorenzo, president of Givenchy Parfums. He said Givenchy was concentrating on the much larger markets for makeup and skin care. “Once we hold a big position in these segments, we will start looking at how to develop perfume as well.”

Mr. Ritter said China was also maturing quickly in regulatory terms, rising toward international standards on allergens and toxicity.

That only means that international brands will try harder to reach Chinese consumers. “I strongly believe that perfume will become more and more attractive to them,” Mr. de Chaudenay said. “China is going to be so big that no one will be able to avoid being in China. We are going there for the long term. We have very ambitious plans.”